Friends of the Earth’s Myriam Douo Talks Monsanto Politics

"When you turn a public health issue with scientific evidence into something that becomes more of a political issue, then the consequences are going to be tremendous."

It’s a critical time for Monsanto as the company faces legal and political battles over the safety of its star herbicide, Roundup.

In the U.S., lawsuits in California allege that glyphosate (the primary chemical in Roundup) causes cancer. Documents recently came to light that allege Monsanto even influenced the EPA to declare the chemical was safe.

While the EPA’s claims that glyphosate is safe look weaker by the day, in Europe the E.U. is poised to vote on the reauthorization of glyphosate. Regardless of which side of the Atlantic it's on, Monsanto’s tactics remain largely the same as it seeks to influence political decision-makers that the most applied herbicide in the world is safe.

We spoke with Myriam Douo, a lobby transparency campaigner and corporate capture expert with Friends of the Earth Europe, to better understand how Monsanto has turned a public health issue into a political game. As Ms. Douo points out, Monsanto’s influence on the world’s food supply could become even greater if its proposed merger with Bayer is approved.

(This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.)

***

Monsanto claims that glyphosate is safe because groups like the U.S. EPA approved it. How would you respond to that?

The scientific evidence is here. The World Health Organization (WHO) did say that glyphosate is a probable cause of cancer in humans, which in our opinion is enough to ban it. The strategy that Monsanto has been using is to discredit those scientific studies by saying that it’s garbage research.

Research in general costs a lot of money. So it’s really hard to find trustworthy, reliable, independent research on glyphosate. Monsanto has been funding a lot of the research.

Agency risk assessments, for instance, are based on documents that Monsanto provided. Companies typically provide the evidence, and agencies conduct an impact assessment using those documents.

But we don’t know what’s in those documents. They’re not available to the public or they’re very, very partially available despite Freedom of Information Act requests. The E.U. Green Party just announced they are going to court over the lack of transparency around the European Food and Safety Authority’s glyphosate review.

Monsanto is a big group with a lot of resources compared to these agencies that rely on the information and resources that Monsanto provides. In reality, the agencies likely did not go through all of the research as they are supposed to.

Friends of the Earth Europe has been especially vocal about the proposed Bayer and Monsanto merger. Why should consumers be concerned?

It’s two agribusiness giants who are going to merge who already have a monopoly in their fields. Bayer specializes in pesticides and Monsanto in genetically modified seeds. Each of them has a major market share and if they merge this is going to become a massive monopoly on food—something that is so basic that we all need.

If all three mergers go through, we’ll have three companies controlling 70% of the world’s agrochemicals and 60% of the seeds.

There’s not only the Bayer and Monsanto merger; there are three mergers happening at the moment of the six big agribusinesses. It’s really important to look at the big picture because it might look like it’s one merger here and one merger there but at the end of the day, if all three mergers go through, we’ll have three companies controlling 70% of the world’s agrochemicals and 60% of the seeds.

It’s especially a problem when you consider Monsanto’s patented seeds. The patents prevent farmers from reusing the seeds from one year to the other, and Monsanto aggressively pressures U.S. farmers for alleged patent infringements. It basically traps farmers to continue buying seeds from Monsanto.

What we advocate for is a system where we have food sovereignty: a system of freedom for everyone to decide what they want to eat without GMOs, without pesticides, without something that’s harmful for people and the planet and our health. These mergers are basically the opposite of that.

How could the mergers potentially give these major agribusinesses greater political influence?

Michael Taylor was responsible for regulation of genetically modified crops, or lack thereof, while having very close relationships with Monsanto.

In terms of political and corporate implications, you have these already massive giants that are going to have even more power.

If you take just a glimpse into the revolving door issue, there’s a very telling case involving Michael Taylor in the U.S. He first started at the USDA, then was a lawyer for Monsanto, then went back to the USDA and the FDA, then back to Monsanto, and then he was appointed by President Obama as a senior adviser to the FDA. He left a few months ago and I’m trying to figure out where he is now but I can tell you it’s not good!

Taylor was responsible for regulation of genetically modified crops, or lack thereof, while having very close relationships with Monsanto. That in terms of corporate capture—the influence of companies on our decision-making processes and our democracies—is really worrying and it needs to ring a very strong bell.

More than 200 organizations around the world petitioned the European Commission to reject these mergers. Unfortunately the first two have been green lighted: Dow Chemicals and DuPont, and Syngenta and ChemChina.

The Bayer-Monsanto merger hasn’t been approved yet. We’re trying to stop the process and prevent that merger from happening. We’re campaigning throughout Europe and around the globe with other groups and NGOs.

What is on our side is that Monsanto has a bad reputation. Luckily they didn’t really manage well in terms of PR. Everybody knows them. Everybody knows what they do. Not a lot of people like them, and rightly so. So hopefully that will work for us to stop this process.

Monsanto and Bayer pledged to divest $2.5 billion of their assets, but regardless, it sounds like they don’t have the public’s best interests at heart.

When companies manage to promote their personal interests over the general interests of the entire population of the planet that is typically a case where corporate capture needs to be fought.

We can’t possibly give these companies more power than they already have. If we want to fix our food system at some point, we need to go in the opposite direction.

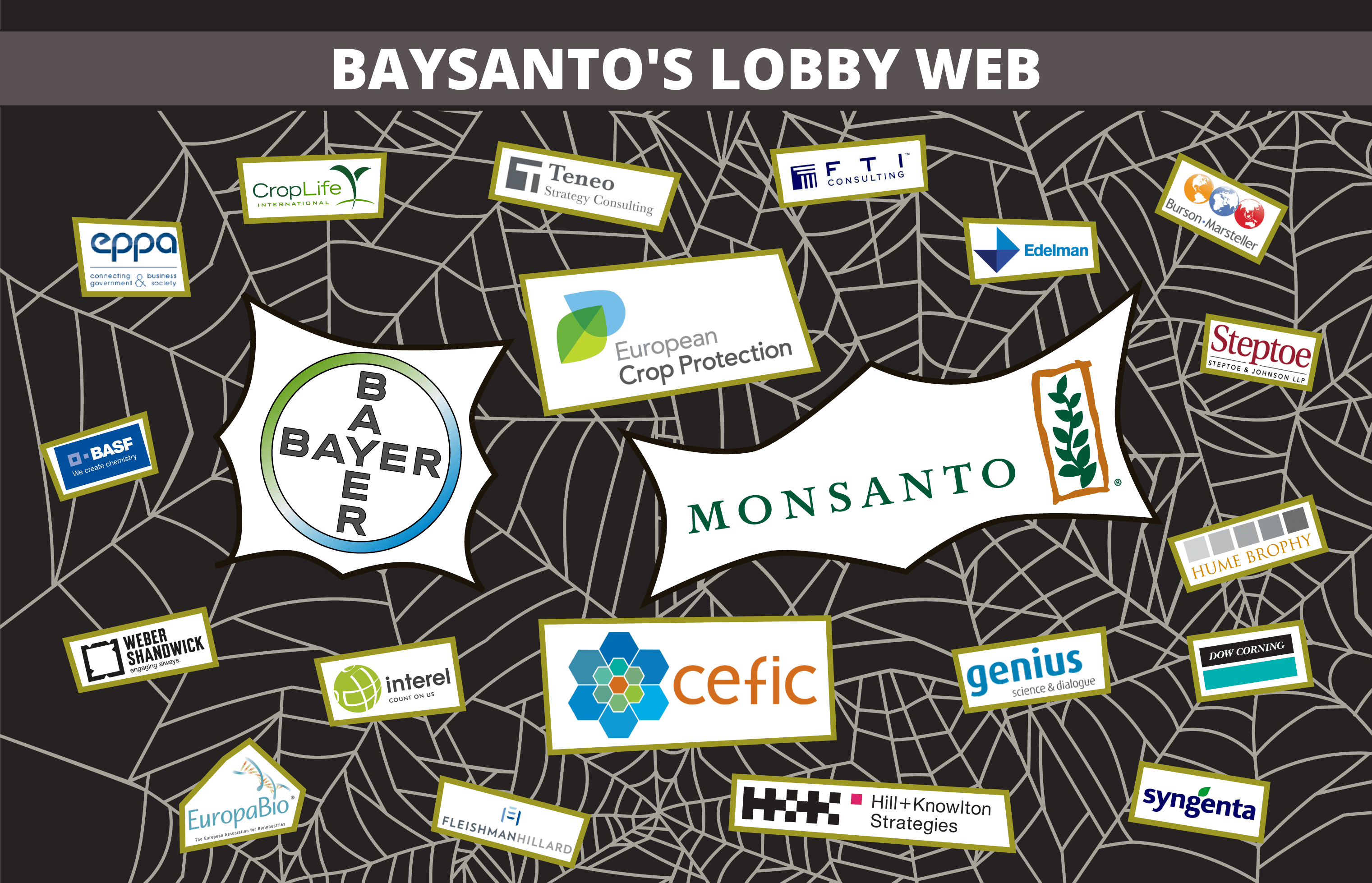

Monsanto and Bayer spend millions on lobbying every year, but you’ve noted that we don’t know how large this sum actually is. Why is this a problem?

Lobby spending is really important because that’s the way we measure an actor’s firepower or influence.

In the E.U., as in the U.S., there’s a register where all lobbyists need to declare what they spend every year both on their direct lobbying and on indirect lobbying. If you pay a PR firm to create a communication campaign, or a law firm to get counsel on the redaction of some bill amendments, or if you are a member of any trade associations who are going to lobby on your behalf, that should count as your lobby power.

In the U.S., the lobby register is legally binding so if you don’t declare your information properly you can receive a penalty.

We know we can’t trust the data but we have no way of knowing exactly how much they spend.

In Europe, we have a voluntary lobby register. The only disadvantage if you don’t register is that you are not allowed to meet the top-level members of the European Commission—the presidents, the commissioners, the director generals, and their cabinets. That’s only about 1 percent of the whole commission. And we all know that the people drafting the legislation are the ones you want to talk to, not the political decision-makers who are only going to rubber stamp the legislation.

The fact that the lobby register is not legally binding also means that all the information that’s declared in it is not reliable. You can compare the U.S. data at OpenSecrets.org and Europe’s on LobbyFacts.eu.

In 2015, Bayer, for instance, declared $7.7 million of lobby spending to the U.S., versus $1 million to the E.U. for an equivalent market. We know we can’t trust the data but we have no way of knowing exactly how much they spend.

How does this lack of transparency ultimately affect consumers?

Everything is so obscure and it’s quite tricky for people to understand or untangle the whole web of interconnections that these companies have.

Ultimately, it’s an issue of public health. And when you turn a public health issue with scientific evidence into something that becomes more of a political issue, then the consequences are going to be tremendous.

Monsanto, for example, created the glyphosate task force in August 2016 and it is solely dedicated to renewing the glyphosate registration in the E.U. It’s a lobby group, clearly, but they are presented as a kind of trade association with members and everything.

Monsanto has also tried to instrumentalize farmers and the agricultural sector. They like to ask, “If we ban glyphosate, how are our famers going to survive and grow their crops?” That’s the strategy of them presenting themselves as “feeding the world” which is not exactly true. Small, non-industrial farmers actually produce more food on less land.

You can understand why they are defending glyphosate because it’s their moneymaker. Monsanto created genetically engineered seeds that are resistant to glyphosate, and farmers use glyphosate to kill weeds. If it’s banned, there’s a whole range of their products that are going to be, not irrelevant, but they will have to start over basically.

But there’s public mobilization around it. A European Citizens Initiative was launched asking the European Commission to ban glyphosate. It has gathered 1.5 million signatures so far.

The awareness is there. People know what it is, which is quite impressive given the technicalities of the topic and the fact that it’s kind of an obscure chemical.