How Workers Are Falling Through the Cracks in the Fissured Workplace

July’s jobs report appeared to be great news for the U.S. economy. It showed that 255,000 new jobs were added—well above economist expectations—while the unemployment rate remains unchanged at 4.9 percent, the lowest it’s been since 2008.

To hear the White House and mainstream media tell it, the jobs report is evidence of America’s continuing strong recovery from the Great Recession. America has added roughly 200,000 new jobs a month for about two years and regained all of the 8.7 million jobs that were lost in the Great Recession (and then some), essentially putting us back at what economists consider to be full employment.

A big part of the jobs story--and one that often goes untold--is job quality, not just job quantity.

Yet the economic view on the ground tells a different story. According to a July 2016 Pew Research Center survey, only 30% of Americans believe that economic conditions in this country are “excellent/good,” while just 1/3 believe that economic conditions will improve in a year. A recent CNN poll found that 56% of Americans think their kids will be worse off financially than them. Shockingly, 47% of Americans responded to a Federal Reserve survey saying they didn’t have $400 in savings to cover an emergency.

This economic unease has fueled anti-establishment presidential candidates Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, both of whom placed messages of economic unfairness at the center of their campaigns. Polls consistently show that the economy is the most important issue of the 2016 campaign, ahead of terrorism, health care, and education.

So what is fueling Americans’ concerns about the economy? Why are so many living paycheck to paycheck in the midst of supposedly improved economic times?

A big part of the story is job quality, not just job quantity. We are seeing the rise of the so-called “contingent worker,” a group that includes contractors and non-traditional workers who aren’t tethered to a single employer—and who also aren’t provided the benefits, legal protections, and security that come with full-time employment. By one estimate, all of the net economic growth of the last decade occurred in contingent work arrangements.

The shift to a contingent workforce is in some respects the result of a changing economy. But companies have also unfairly eliminated labor costs by shifting employment to other parties and misclassifying employees as independent contractors.

The Department of Labor considers employee misclassification a serious problem that harms the entire economy and is cracking down on the practice. Recent court rulings may also make it more difficult for companies that depend heavily on independent contractors to avoid responsibilities to workers through outsourcing. Additional challenges to harmful employer practices such as misclassification makes it incumbent upon workers to know the law and understand their rights.

The “Fissured” Economy

David Weil literally wrote the book on how companies’ outsourcing of work has changed not only the economy, but the nature of employment.

“The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became So Bad for So Many and What Can Be Done to Improve It” landed Weil, a former economics professor at Boston University, a job as head of the Wage and Hour Division at the Department of Labor.

“Our basic mission at Wage and Hour is pretty simple: making sure people get a fair day’s wage for a hard day’s work,” said Weil. “The difficulty is the workplace has changed dramatically in the last 20 years.”

In Weil’s view the workplace has “fissured” as companies, responding to changing market pressures, cut labor costs as part of a broader strategy to become leaner and more agile, in the process shedding their role as direct employers of workers.

Throughout most of the 20th century market changes were slow and incremental, and consumer tastes were relatively simple. Production was based on a “push” strategy of forecasted demand. This allowed companies to focus on economies of scale, or gaining a cost advantage via increased output.

Work, reflecting these trends, was repetitive but stable. Workplace technology changed slowly, with workers provided ample time to learn new skills. The main employment relationship was between large businesses—such as General Motors, US Steel, IBM, and Xerox—and the workers that made their products. Direct, long-term employment with a single company was the norm.

All of this began to change in the late 1980s and early 1990s as globalization and technology reshaped the economy. Operating in tandem, these forces expanded the competitive landscape and created virtually endless new market opportunities.

More sophisticated consumers began a shift to a “push” economy. Change became fast, dynamic, and constant. Facing increasing pressures to adapt to market changes, businesses began to shed activities considered peripheral to their core business models, shifting their focus to product differentiation and market niches. Maintaining brand integrity (and thus loyal patrons) and driving down costs emerged as the pillars of success in this new economy.

Unfortunately for workers, they are viewed as low hanging fruit when it comes to cost cutting. Keeping a full-time workforce is expensive. Employee expenses such as federal (FICA) payroll taxes, unemployment and workers’ compensation insurance contributions, health and retirement benefits, and paid time off add 25% - 30% to payroll costs. Only employees are required to be paid the minimum wage and overtime, and employees have much more robust legal protections for things like workplace accidents, discrimination, exploitation, and wrongful termination.

Businesses realized they could farm out to a network of providers jobs that were once handled internally. In so doing they created competitive markets for services that allowed them to eliminate direct employment costs.

In short, businesses still receive the benefit of workers’ labor without serving as their employer of record and assuming additional financial liabilities. Using business models such as subcontracting, temp agencies, labor brokers, franchising, and third party management, companies push apart the longtime bedrock of the U.S. economy—the employer-employee relationship—leading to what Weil calls the “fissured” workplace.

Weil admits that fissuring does not always result from companies’ desire to avoid payroll costs. As markets have changed, so have the role of workers. A static workforce doesn’t make as much sense in a business environment requiring continual reflection and reorganization. The rigid, 9-5 enterprise structure of employment is becoming obsolete. In today’s leaner enterprise, teams are formed around projects that make use of contingent labor and independent experts. Once a project is completed, teams can be disbanded and new ones formed on an ad hoc basis.

From this perspective, contingent workers increase business efficiency, agility, and flexibility. They not only cost less than employees, but also turn employment expenses into variable costs for services, rather than fixed labor costs.

Weil believes, however, that this model allows companies to have their cake and eat it too. By calling some workers “independent contractors” and hiring others through agencies, companies are able to avoid some of the burdens—but not the benefits—of having employees. Contingent workers contribute to building a brand that reaps great profits for the lead company, but don’t receive job-based health and retirement benefits or the minimum wage, overtime, and other labor law protections.

Rise of the Contingent Worker

To illustrate the workplace that has cracked and split apart, Weil uses the example of a hotel operating under a well-known international brand. The workers who greet guests, clean rooms, landscape, and prepare food are likely not hotel employees, or even employees of the hotel brand. They are more likely employed by another business offering hotel management services.

“All of the net employment growth in the U.S. economy from 2005 to 2015 appears to have occurred in alternative work arrangements.”

Such blurred lines of employment are not limited to the hospitality industry. Awareness has grown of the reliance on contract labor in the so-called “gig economy” comprised of tech industry startups companies such as Uber, Lyft, Handy, and Taskrabbit. But it’s also the workers who deliver packages, install cable and internet, drive taxis, provide security, perform construction work who have an arm’s length relationship with those companies that appear to employ them. In fact, even professionals such as doctors, lawyers, financial advisers, and education and health service providers are falling through the employment cracks.

Identifying the size of the contingent workforce is tricky due a lack of standardized terminology. Depending on the definition used, contingent workers make up less than 5% to as much as 40% of the total labor force. Estimates are also difficult in the absence of comprehensive, nationally representative data.

From 1995 to 2005 the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) administered a survey known as the Contingent Work Supplement (CWS), a supplement to its monthly Current Population Survey (CPS). BLS administered the CWS in 1995, 1996, 1999, 2001, and 2005. Since 2005 BLS has not received funding to administer the supplement.

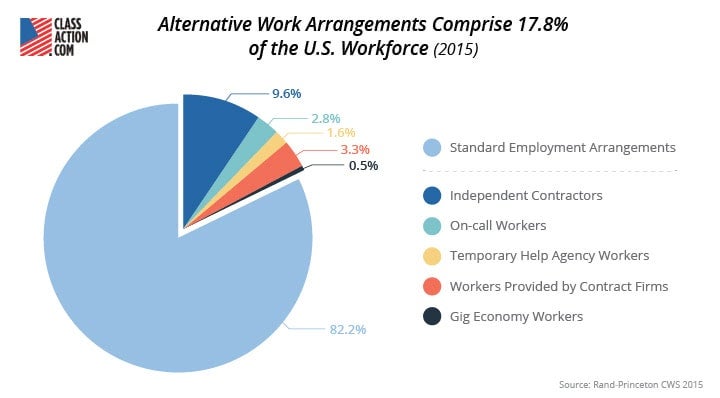

In the absence of the CWS public and private organizations have attempted to fill in data gaps. The RAND Corporation, for example, conducted a version of the CWS that counted workers engaged in “alternative work arrangements,” defined as temporary help agency workers, on-call workers, contract company workers, and independent contractors (freelancers). The Government Accountability Office (GAO), relying on data from the CWS and other government surveys, uses these same categories of alternative work arrangements but adds to them self-employed workers and part-time workers.

Using GAO’s definition of alternative work arrangements, contingent workers comprised 30.6 percent of the labor force in 2005 and 40.4 percent in 2010. Contract company workers, on-call workers, and agency temps—what GAO calls “core contingent arrangements”—made up 5.6% of the workforce in 2005 and 7.9% in 2010.

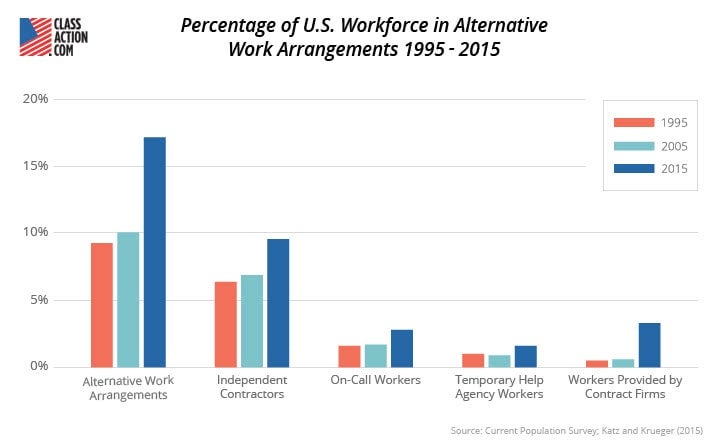

RAND, comparing BLS CWS data to figures derived from its 2015 RAND-Princeton Contingent Worker Survey (RPCWS), found a rise in the incidence of alternative work arrangements from 10.1% in 2005 to 17.2% in 2015—an increase of more than 50 percent. Using combined CWS/RPCWS data shows that from 1995 to 2015 the proportion of workers in alternative work arrangements increased by nearly 85% (9.3% to 17.2%).

The Great Recession appears to have accelerated the trend towards companies hiring more contingent workers. According to RAND, from 2005 to 2015 total U.S. employment increased by 9.1 million (6.5%), but traditional full-time employment actually declined by 0.4 million (0.3%). These estimates caused RAND to speculate that “all of the net employment growth in the U.S. economy from 2005 to 2015 appears to have occurred in alternative work arrangements.”

And the growth continues. Enterprise software company Intuit says that more than 80% of large corporations plan to substantially increase their use of flexible workers in coming years. Intuit predicted in 2011 that by 2020, contingent workers will exceed 40% of the workforce—an estimate that is already outdated. Many now expect that at the turn of the next decade contingent workers will make up 50% of the workforce.

Independent Contractors in Focus

The most common form of alternative work arrangement is independent contracting. Definitions of independent contractors (ICs) vary depending on context. The BLS, GAO, and RAND generally agree that ICs “obtain customers on their own to provide a product or service.” Business consulting services group Navigant specifies that ICs:

- Work at multiple projects simultaneously

- Move frequently from project to project

- Exercise significant autonomy relative to their “client”

- Often bring their own tools or equipment to the project

Independent contractors are considered to be “self-employed,” but not all self-employed workers (such as restaurant owners) consider themselves to be independent contractors. ICs may also be referred to as “independent consultants” and “freelancers.”

Insofar as ICs are differentiated from employees, the surest means of identification is how income is reported. Unlike employees, who report income on an Internal Revenue Service (IRS) Form W-2, independent contractors report income on Form 1099-MISC.

Approximately 1 out of 10 U.S. workers is considered to be an independent contractor. Varying definitions and data sources make it tough to pin down the precise number, however. GAO data puts the number of ICs as high as 15-16% of the labor force, while RAND data has the number of ICs at 9.6% of the labor force (as of 2015).

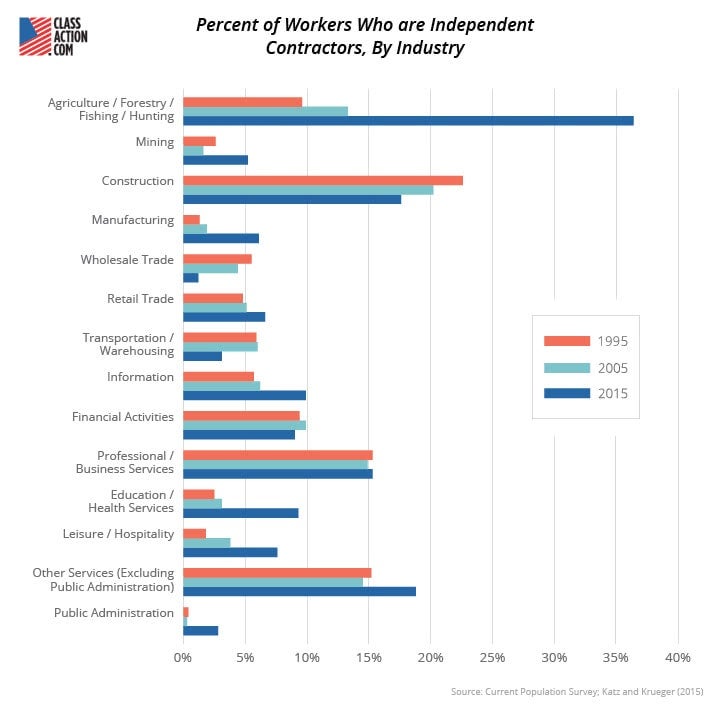

The total percentage of ICs in the workforce increased by about 50% from 1995 to 2015. IC characteristics have also changed, most notably in relation to gender and occupation. Although the number of male ICs has remained stable at around 8-9% of all workers, the number of female ICs has nearly doubled over the last 20 years. Industries that have shown the largest shifts in IC workers include Construction (down 5%), Manufacturing (up 4.8%), Education and Health Services (up 8.8%), and Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting (up 26.8%).

Employees or Independent Contractors?

The use—and misuse—of independent contractors is a topic of considerable controversy.

On the one hand, surveys show that many workers prefer independent contractor relationships to employment relationships. The BLS reports that 82.3% of ICs prefer working independently to being an employee. A Pew Research Center survey found that 39% self-employed workers are “completely satisfied” with their jobs compared to 28% of employees. Flexibility, autonomy, and a path to entrepreneurship are cited as the top reasons why workers prefer independent contracting.

Compared to employees, contingent workers earn less and receive fewer benefits, have less economic security, and are more likely to require public assistance.

For skilled workers who reap the benefits of selling their services to businesses while maintaining autonomy, self-employment can indeed be a profitable career path. Yet other workers are caught in a grey area between employee and independent contractor. They may be economically dependent on and have their work controlled by a single company that appears to be an employer, but that company might consider them a contractor, not an employee. An estimated 10-30% of employers misclassify their employees as independent contractors.

The intentional misclassification of employees as independent contractors is a problem for workers, governments—and if they’re caught breaking the law—employers. While the practice allows employers to save 25-30% on payroll costs, it denies misclassified employees access to benefits and protections. Research shows that, compared to employees, independent contractors and other contingent workers earn less and receive fewer benefits, have less economic security, and are more likely to require public assistance. Misclassification also results in lower tax revenues and losses to state unemployment and workers’ compensation funds.

Governments Crack Down

Lax enforcement of independent contractor laws prevailed throughout the 1990s and the early 2000s, but since 2007 federal and state regulators have been cracking down on misclassification.

The Department of Labor has been hiring more investigators to “detect and deter” misclassification, prosecuting more companies believed to be misclassifying workers in order to avoid paying overtime and the minimum wage, and providing grants to state workforce agencies to increase enforcement efforts.

DOL refers to these efforts as a “Misclassification Initiative.” From 2009 to 2015 the agency estimates it has recovered nearly $1.6 billion in back wages for 1.7 million workers. The IRS, through its Questionable Employment Tax Practices program, Voluntary Classification Settlement Program, and regular audit processes has likewise sought to crack down on employee misclassification. Many state workforce agencies, particularly in left-leaning California, Massachusetts, and New York, have also been diligent in pursuing businesses believed to be misclassifying employees as independent contractors.

Independent Contractor Misclassification Lawsuits

Workers are increasingly taking matters into their own hands and challenging their status as independent contractors in class action lawsuits.

Misclassification lawsuits have been on the rise in recent years, with high-profile cases filed by couriers, exotic dancers, and drivers for on-demand ride companies Uber and Lyft, among others.

In 2016 alone, FedEx, Uber, and Lyft have reached settlements with workers worth $240 million, $100 million, and $27 million, respectively.

These cases reveal a common thread used to determine whether a worker is an employee or a contractor: the degree of employer control over the manner in which work is performed.

FedEx ground workers argued that they were employees because FedEx assigned them specific routes, required them to check in with managers at the start of the day, and regulated their appearance and equipment. Uber and Lyft drivers similarly argued that they were subjected to a litany of detailed requirements that, if not followed, could result in their termination. Even exotic dancers have used these arguments to win misclassification cases, saying that they were denied flexibility in their choice of working schedule, told how to dress, and made to perform a certain number of dances.

But settlements, although they can provide compensation for workers in the form of back wages and expense reimbursement, usually don’t provide clarity on worker status because companies often agree to a settlement only if they are allowed to continue treating workers like independent contractors. As part of the Uber and Lyft settlements, for instance, drivers remain independent contractors. In contrast, when a case is decided at trial, the court is allowed to rule on whether a worker is an employee or a contractor, which can lead to a worker receiving significantly more protections moving forward.

Misclassification lawsuits are typically filed in federal court under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), a federal law that guarantees employees the federal minimum wage and overtime pay for more than 40 hours worked in a week. Because many states have minimum wage and overtime laws that are more generous than federal laws, workers may also bring state-level misclassification lawsuits. In most wage and hour cases plaintiffs file in federal court under both federal and state claims.

Since wage and hour laws only apply to employees (and not contractors), the key determination in these cases is whether a worker is an employee or an independent contractor. The FLSA uses a six-factor “economic realities” test to determine whether an “employment relationship” exists. This interpretation centers on the degree to which a worker is economically dependent on the business of the employer. All of the factors are considered in each case, and no single factor is determinative by itself.

Some states have their own labor laws and tests that are used to determine employment status. California begins with the presumption that the worker is an employee and uses an 11-factor economics reality test adopted by the California Supreme Court. Massachusetts has adopted an independent contractor law with a stringent 3-factor test that requires businesses to overcome a “presumption” of employee status.

Legislation

New laws may ultimately be needed to address employee misclassification and other worker issues in the fissured economy.

Most worker protection laws were drafted decades ago, when the economy was starkly different than it is today. The FLSA was passed in 1938, a time when the U.S. economy was manufacturing-based, children were working long hours in factories, and the minimum wage was 10 cents per hour.

Legal experts have noted how the FLSA—which only applies to “employees” working for companies with a minimum business volume of $500,000—has contributed to misclassification and the farming out of labor to smaller companies. These provisions create incentives for businesses to shed employees, designate others as independent contractors, and hire temps. They additionally have led employers to use holding companies, shell operations, franchises, and other creative structures to avoid wage and hour laws on the grounds that each entity is an independent employer that does not reach the $500,000 threshold. These same entities might argue that they don’t meet the requisite number of employees needed to comply with the Family Leave and Medical Act (FMLA).

A recent National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision on contract labor could make it more difficult for companies to avoid legal responsibilities through outsourcing. NLRB voted in August 2015 to adopt a more expansive definition of what it means to be a “joint employer,” which should make it easier for contingent workers to organize their labor under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), which applies only to employees.

The case arose when a Teamsters local union argued that bargaining wouldn’t be effective unless it was able to negotiate with both a recycling company and the temporary staffing agency that provides its workers. NLRB agreed with the union’s assertion that the larger company determined working conditions and therefore should be considered a joint employer, saying that “its previous joint employer standard has failed to keep pace with changes in the workplace and economic circumstances.”

Since 2007 more than a dozen federal bills addressing independent contractor misclassification have been proposed and dozens have passed at the state level

On the misclassification front, since 2007 more than a dozen federal bills addressing independent contractor misclassification have been proposed and dozens have passed at the state level, from the Northeast to the Mountain West to the Deep South.

The Payroll Fraud Prevention Act, proposed in 2013 and again in 2014, sought to make the intentional misclassification of employees a federal offense, amend the FLSA to include a new category of workers (“non-employees”), and require every employer to inform employees and non-employees of their legal rights. In 2015 Congress introduced the Independent Contractor Tax Fairness and Simplification Act, a bill that acknowledges the important role legitimates ICs play in the economy but limits the definition of IC under the safe harbor provision of the Internal Revenue Code.

Congressional paralysis makes IC legislation unlikely before the 2016 elections. States, on the other hand, have proven to be much more successful at passing laws designed to curtail employee misclassification.

Modernizing regulatory policies and laws is necessary in a new economy that in many respects bears no resemblance to the old economy. As the nature of work changes, government has to change, too.

However, the question must be asked: can governments keep pace with the rapid changes that technology and globalization have made possible…or are they destined to remain one step behind?

David Weil of the Department of Labor believes that, despite the complications a changing workplace poses, government still has an important role to play in establishing norms of fair treatment. Fairness, he says, is a basic human idea. When a business creates value but the people who do the work don’t share equally in the profits, as occurs in the fissured workplace, income inequality and a general sense of unfairness results, often with wider political and social implications.

But in an economy that is pushing people towards ever-greater autonomy, it’s equally important for workers to know their rights and be their own best advocate. It is workers who have lost the most from workplace fissuring. And it is workers who have the most to gain from ensuring they receive a fair day’s pay for a hard day’s work.