This Is How Opioid Lawsuits Differ from Big Tobacco's

If 2017 was the year the opioid crisis was recognized as a public health emergency, then 2018 may be the year we begin producing solutions to the crisis.

To that end, opioid litigation—which combines more than 200 government lawsuits against dozens of companies and individuals—is one of the most promising developments.

The judge overseeing the federal opioid lawsuit said on January 9 that he hopes a sweeping resolution with a “meaningful impact” can be worked out by the end of the year.

Opioid litigation and tobacco litigation share many similarities, but there are also significant differences.

“We have to dramatically reduce the total number of pills out there, and make sure the pills that are out there are being used properly,” said U.S. District Judge Dan Polster of Ohio in his Cleveland courtroom. The judge likened the opioid crisis to the 1918 flu epidemic that killed hundreds of thousands of Americans while making the important distinction that this epidemic is “100 percent man-made.”

Litigation to combat a public health problem is not without precedent. Hopes are high that opioid litigation will produce a settlement on par with the Big Tobacco settlement of 1998, which saw tobacco companies pay billions of dollars to states to cover the costs of smoking.

ClassAction.com attorneys like Keith Mitnik helped lead the fight against tobacco companies, and they are playing a prominent role in opioid lawsuits. Opioid litigation and tobacco litigation share many similarities, but there are also significant differences.

Now we will explain the current wave of litigation, compare it to tobacco cases, and explain how governments might use settlement money to fight the opioid crisis.

Governments Sue to Recover Costs of Opioid Harms

Kentucky’s Attorney General, Andy Beshear, filed a lawsuit against Endo Pharmaceuticals (maker of opioid drug Opana ER) on November 6, 2017 to “hold Endo responsible for unlawfully building a market for the chronic use of opioids in the name of increasing corporate profits, knowing all along the dangers of Opana ER that led to devastating effects on the Commonwealth.”

Hundreds of local governments are suing the opioid industry to recover costs related to the crisis.

Beshear, with help from ClassAction.com attorneys like James Young, seeks compensation on behalf of the Commonwealth for increased costs to the state. These include costs from emergency room visits, emergency responses to overdoses, the administration of anti-overdose drug Naloxene, Hepatitis C from intravenous opioid use, drug-related crimes, and other harms. Kentucky claims these damages are the result of Endo’s allegedly deceptive, aggressive, and illegal opioid marketing.

“This action seeks repayment of the Commonwealth’s spending on opioids, disgorgement of Endo’s unjust profits, civil penalties for its egregious violations of law, compensatory and punitive damages, injunctive relief, and abatement of the public nuisance Endo has helped create,” states the lawsuit.

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is joined in its legal battle by many Kentucky cities and counties that similarly seek to recoup the costs of the health crisis that has devastated their communities.

Nationwide, hundreds of states, cities, counties, and even Native American tribes are suing the opioid industry for addiction costs for which they say the opioid industry is responsible. Some, like the Kentucky AG’s suit, name a single defendant. Others name a dozen, from manufacturers and distributors to doctors and clinics.

These lawsuits have been consolidated in Ohio federal court as part of multidistrict litigation (MDL) before Judge Polster. According to an order establishing the MDL, the opioid lawsuits consolidated in the Northern District of Ohio contain “common questions of fact,” including:

- Prescription opioid manufacturers overstated the benefits and downplayed the risks of using opioids and aggressively marketed the drugs.

- Distributors failed to monitor, detect, investigate, and report suspicious orders of prescription opioid painkillers.

Since opioid manufacturers and distributors are the primary defendants named in lawsuits, their alleged roles in the opioid crisis deserve a closer look.

Claims Against Opioid Manufacturers

Purdue Pharma, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Endo Health Solutions, Allergan PLC, and Actavis, Inc. are among the drug companies named as defendants in opioid litigation.

The allegations made against drug companies are virtually identical. A State of Ohio lawsuit, for example, makes the typical assertions that manufacturers

- Engaged in a deceptive marketing scheme designed to change opioid prescribing patterns (from end-of-life care only to “chronic pain”). This greatly broadened the pool of patients to whom opioids could be prescribed and led to a huge increase in profits for opioid manufacturers.

- Downplayed the addiction risks and overstated the benefits of opioid painkillers.

- Worked through third parties—including front groups and key opinion leaders—to disseminate their misleading messages about opioids.

- Placed their desire for profits above the health and well-being of their customers and the communities where they live, and in so doing unleashed a public healthcare crisis with extensive financial and social consequences.

- Caused substantial economic injury to state, city, and county agencies.

The Ohio lawsuit seeks damages from drug manufacturer defendants to pay for opioid-related costs such as increased spending by the state’s Medicaid department, workers’ compensation bureau, drug treatment and counseling services, child protection agencies (due to parental drug addiction), emergency medical services, and law enforcement responding to a surge in drug abuse and crime.

Claims Against Drug Distributors

Drug manufacturers are not permitted to sell their products directly to pharmacies. They must use a distributor (wholesale) company that serves as an intermediary between manufacturer and pharmacy.

Lawsuits claim that distributors helped fuel the opioid crisis because they failed to properly monitor drug shipments.

The major distributors of opioid painkillers are AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson Corporation. Because drugs like oxycodone and hydrocodone are controlled substances, licensing regulations impose duties on distributors to provide effective controls and procedures to prevent theft and diversion of opioids.

Lawsuits, including a case filed by New Mexico, claim that these distributors played a crucial role in perpetuating the opioid crisis because they violated these duties and allowed opioid diversion to flourish.

New Mexico accuses drug distributors of the following:

- Selling huge quantities of prescription opioids that were diverted from lawful medical purposes

- Breaching their legal duties to prevent diversion

- Failing to report suspicious opioid orders (orders of unusual size, orders of unusual frequency, and orders deviating substantially from a normal pattern)

- Failing to monitor, detect, halt, investigate, and refuse suspicious orders

- Misleading the public about complying with their obligations to meet licensing regulations

- Causing substantial economic damages to state and local governments due to their breaches of legal duties

The New Mexico lawsuit seeks economic damages from drug distributor defendants as reimbursement for the costs associated with past—and ongoing—efforts to eliminate the hazards of opioid proliferation to public health and safety, including from prescription opioid and heroin abuse, addiction, morbidity, and mortality.

It names manufacturers and distributors as defendants and calls for a “multifaceted, collaborative public health and law enforcement approach” focused on preventing new cases of addiction and ensuring access to addiction treatment. The complaint notes “budgetary constraints at the state and Federal levels” that limit solutions.

“Having profited enormously through the aggressive sale, misleading promotion, and irresponsible distribution of opiates,” says New Mexico, “Defendants should be required to take responsibility for the financial burdens their conduct has inflicted.”

Comparing Opioid Litigation and Tobacco Litigation

In November 1998, the Attorneys General of 46 states, five U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia reached a $246 billion settlement with the five largest American tobacco companies. Tobacco companies agreed to divert revenues to states over the ensuing 25 years and to impose restrictions on the sale and marketing of cigarettes.

The landmark settlement was borne of an ingenious legal strategy. Dying smokers and their families filed hundreds of lawsuits against tobacco companies, but juries always found that smokers were responsible for smoking.

Tobacco companies reached a $246 billion settlement with 46 states, five territories, and the District of Columbia.

To deny the tobacco industry its traditional defense, state attorneys decided to sue companies to recoup the costs to Medicaid programs of treating smoking-related ailments (such as heart disease), since treatments left many smokers penniless and these programs had to bear the remaining costs. The state attorneys hired outside counsel on a contingency-fee basis to bring cases on behalf of governments.

With opioid lawsuits gaining momentum, some observers have suggested that litigation against the opioid industry is the second coming of tobacco litigation. On its face, this comparison is accurate: governments are hiring firms on a contingency-fee basis to sue private companies and recoup the costs of a public health problem caused by an addictive drug whose dangers companies allegedly concealed.

A more careful analysis, however, reveals many key differences between tobacco and opioid litigation.

Cities and counties are involved in opioid litigation

Tobacco lawsuits were brought on behalf of states to recoup Medicaid payments tied to smoking. States have filed opioid lawsuits, but cities and counties—which have dealt with the costs of opioid addiction on a non-Medicaid basis—are also a part of the litigation.

"An important distinction between this litigation and tobacco is that the local municipalities are serious players in seeking to recoup their expenses and to get help paying for the solutions in their community," said ClassAction.com attorney James Young.

The different types of plaintiffs and alleged harms makes opioid litigation much more complicated than tobacco’s. It could make it more difficult for plaintiffs to cooperate and agree on a mutually satisfactory settlement.

"This could prove interesting when it comes time to settle, since each community will have unique needs and plans," said James Young. "In tobacco, the plaintiffs were the state attorneys general, which were more cohesive in what they sought."

Opioid litigation names numerous defendants

Tobacco litigation focused on just a handful of companies that manufactured their own products and sold them directly to consumers. In the case of opioids, there are opioid manufacturers, the companies that distribute opioids, the clinics that sell them, and the doctors that prescribe them. This adds another layer of complexity to the litigation that wasn’t found in tobacco cases.

Tobacco and opioid painkillers are very different products

A major difference between tobacco and opioids is that the former has no legitimate medical uses. Opioids, however, are an important pain medication for many patients. Some patients who say they need opioids and have used them for years without problems complain that they are now unable to get the drugs due to crackdowns. Reforms resulting from a settlement might only exacerbate this problem.

Another major issue is that, unlike tobacco, opioid painkillers were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and included certain regulations and warnings. This could allow defendants to "shift some of the blame to the federal government," as NPR's Ailsa Chang suggested.

The tobacco industry is wealthier

Even if a settlement is reached in opioid litigation, the plaintiffs probably shouldn’t expect a payout rivaling the one from Big Tobacco, an industry that, despite the hits it has taken over the last couple of decades, is still enormously profitable.

The U.S. opioid market generates around $10 billion in annual gross sales. Big Tobacco had nearly $20 billion in net profits in 2016. For comparison, OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma has about $3 billion in annual revenue. That’s certainly no pittance, but it raises the question of whether enough money can be collected from the opioid industry to help solve the problems it allegedly fostered.

There were tobacco industry whistleblowers

Plaintiffs had a secret weapon in tobacco litigation: whistleblowers who produced internal documents from tobacco companies showing that they hid evidence of the risks and addictiveness of smoking.

It’s possible that whistleblowers from drug companies will play a similar role in opioid litigation, but so far, none have come forward with damning evidence (although an ex-DEA whistleblower has some pointed things to say about the drug industry and Congress).

It All Depends on How the Money is Spent

One of the biggest lessons learned from tobacco litigation is that it isn’t how much money plaintiffs receive—it’s how they spend that money.

Data on state spending of money from the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement shows wide variability in how states spent money that was supposed to be used fund Medicaid services and anti-smoking education programs. The money often went elsewhere.

"If you're going to get the money... don't let it be used by whatever the legislature wants."

For example, as of 2010 California had received $401,637,000 from tobacco companies—and spent every cent on debt servicing/budget shortfalls.

Jim Tierney, former Attorney General of Maine, told NPR that “if you’re going to get the money, don’t make the mistake in tobacco and let it be used by whatever the legislature wants. They’ll use it to pave roads… or lower taxes or something preposterous when we have a huge health crisis.”

What Happens Next

In the event that plaintiffs and defendants cannot reach a settlement in the opioid MDL, individual lawsuits would be returned to their local jurisdictions and tried by those courts. But the unknowns of a jury trial could convince both sides that a settlement is the more prudent option.

Opioid defendants may want to avoid facing juries from opioid-ravaged communities, as those who decide their legal fate could very well have lost loved ones to the crisis. At the moment, though, they appear to hold a crucial edge in public opinion.

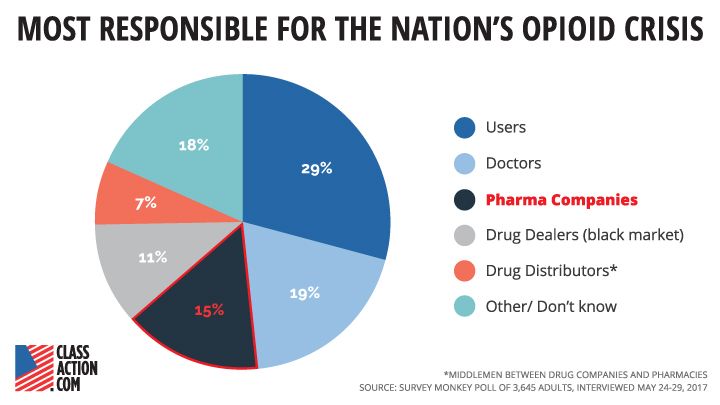

A 2017 poll found that respondents primarily blamed patients and doctors for the nation’s opioid crisis. Fifteen percent said that drug companies were most responsible, while seven percent primarily blamed drug distributors.

Companies are keenly aware of public opinion and how it impacts their bottom line. Deep public mistrust of tobacco companies was a crucial factor in the decision of company officials to settle. They knew that facing juries could be more costly than settling, that it might even lead to bankruptcy.

As lawsuits proceed, however, evidence may emerge that reveals harmful, unethical, and illegal business practices that turn public opinion against opioid companies.

At the same time, plaintiffs have no guarantees that a trial will produce favorable results—that is, if they even get that far. While there is a precedent of opioid manufacturers and distributors settling state lawsuits involving similar allegations for hundreds of millions of dollars, the companies admitted no fault. Still, they produced funds that governments desperately needed to deal with the opioid crisis and resulted in changes to industry practices.

Opioid plaintiffs and defendants in the current MDL have already begun settlement discussions. How they end is anyone’s guess, but win or lose, lawsuits against the opioid industry show that communities are serious about solving the worst drug crisis in America’s history.